Monday, December 29, 2014

Silver John (or John the Balladeer)

Back during my pre-Halloween enjoy-spooky-stories period I was also getting into old folk recordings and roots music, and it was the absolutely perfect time to be introduced to Manly Wade Wellman's SILVER JOHN character, which combines the two. Ive read the first story collection and have tracked down the first three novels, which I'm looking forward to reading as soon as my schedule permits.

Friday, December 19, 2014

Revisiting the Scene Puzzle

When it comes to how we approach our work, some cartoonists

are analytical, some of intuitive (which is a less clunky way of saying

UNCONSCIOUSLY analytical; there’s still a lot of learning and decision-making

going on, it’s just internalized). Most

have one foot in the other camp to some degree, but I think that the majority

either do things because they feel right and practice and experience and taste

let us know whether or not we’re making the right decision, or we make our

decisions based on considered principles that we’ve either learned or created

for ourselves. I expect that much of an

artist’s self-improvement over the years is based on his or her ability and

willingness to lean ever further away from that natural inclination, steadily

absorbing the principles of the other side.

I’m analytical, which I found to be a real boon to my teaching experience. And I was really excited about teaching a graduate course called “Exploring the Narrative.”

I took this same course when I was in grad school, and it

was a train wreck. We learned…

Nothing.

Seriously, nothing (life lessons aside). That’s not an

exaggeration. At a certain point in the

class, well past the halfway five-week mark, another student (more outspoken than

myself, which isn’t something I general encounter) asked directly “are we going

to learn how narratives work?”

When pressed as to what he meant, he, and the rest of us, got more specific: are we going to learn any principles, any

philosophy or technical approach that will allow us to approach narrative with

any sort of foundation that we can use to build our stories? The teacher, irritated, said “Well, I guess

not. No.” Most (maybe all, but I doubt it, and can’t

remember) of the class walked out. Most

of us were absolutely bristling with rage at the refusal of our teacher to familiarize himself with the concepts that he was charged with imparting to us.

I had never read McKee, or Field, or Campbell, or anyone

else like that; I didn’t know that they existed. But I had a belief that storytelling, like

anything else, must have foundational principles upon which to build, hard

rules from which one could, of course, deviate… but I hadn’t the slightest idea

what those rules were, and the class in which I expected to learn them did not

deliver.

I was making my first “real” book, Crogan’s Vengeance (soon to be released in a new color version

retitled Catfoot’s Vengeance), at this time, in

grad school. I was doing my best to be

analytical about its structure, but I lacked the tools with which to approach

it the way I wanted. So I considered my

favorite comic, Jeff Smith’s Bone. A Bone

trade collection was made up of six issues.

So I decided to have five cliffhanger moments and a climax, each at

roughly twenty-four page intervals. That

was the extent of my structure.

And so I approached the book more intuitively than I

otherwise might’ve. Luckily, intuitively

doesn’t mean thoughtlessly. I, like most

of us, had internalized a lot of storytelling principles through the narratives

that I had consumed. And so the book,

while as flawed as anything I’ve done, holds up much better than I would have

thought it might given how I was flying blind the whole time.

Anyway, when I was pegged to teach the class a few years later, I decided that it was to be the complete opposite of the class that I had taken. If there was going to be a narrative course, then by God we would understand the foundational principles of narrative.

Each year I built up the class (and my own knowledge) a little more, started compiling the best bits from different writers and theorists, delving into as much literary theory as I could and trying to give the students something of a humanities primer (a subject not required by the college, which infuriated, and still infuriates, me… half a dozen required esoteric art history courses but they’re never expected to learn the standard stuff that folks assume you’ve gotten with your higher education), touching on Aristotle’s poetics and Horace and Longinus and Pope and Shakespeare, anything applicable. We mushed up Story and Save the Cat and Screenplay and Mamet and talked about how Campbell is only applicable when dealing with two of Frye’s five modes of literature and how the Abrams classification of theories is a direct corollary to McCloud’s Four Tribes of Comics and why a teaser intro is a good idea in a genre story and how Galaxy Quest improves upon the Chekhov’s Gun principle and… a lot of stuff. And man, I loved that class. I absolutely loved it. I was lucky to always have enthusiastic, engaged students, but everyone was always at the top of their game in narrative and its undergraduate parallel Scriptwriting.

Anyway, when I was pegged to teach the class a few years later, I decided that it was to be the complete opposite of the class that I had taken. If there was going to be a narrative course, then by God we would understand the foundational principles of narrative.

Each year I built up the class (and my own knowledge) a little more, started compiling the best bits from different writers and theorists, delving into as much literary theory as I could and trying to give the students something of a humanities primer (a subject not required by the college, which infuriated, and still infuriates, me… half a dozen required esoteric art history courses but they’re never expected to learn the standard stuff that folks assume you’ve gotten with your higher education), touching on Aristotle’s poetics and Horace and Longinus and Pope and Shakespeare, anything applicable. We mushed up Story and Save the Cat and Screenplay and Mamet and talked about how Campbell is only applicable when dealing with two of Frye’s five modes of literature and how the Abrams classification of theories is a direct corollary to McCloud’s Four Tribes of Comics and why a teaser intro is a good idea in a genre story and how Galaxy Quest improves upon the Chekhov’s Gun principle and… a lot of stuff. And man, I loved that class. I absolutely loved it. I was lucky to always have enthusiastic, engaged students, but everyone was always at the top of their game in narrative and its undergraduate parallel Scriptwriting.

I feel like one of the most important parts of teaching is

making the effort to quantify everything.

To establish rules for why something works. If it deviates from those rules and still

works, then we have to be able to ascertain the reason. If it follows the rules and fails, we have to

be able to understand why and establish further parameters inside which failure

is less likely to occur.

This may sound like it’s the easiest way to suck the

fun/life/artistry out of storytelling, and it’s probably the mindset that

drives the economics of the Hollywood studio system that is so often lambasted

for simplifying process down to formula.

But when your goal is to make good stories then you (or at least I) want

all the tools at my disposal. I may not

use all of them (and much of my last year has been an attempt to lighten the

tool box, to extend the analogy) but I want to have them so that I can make a

conscious choice as to whether or not I’ll use them.

One of the things

that I did, for myself and for the class, was to work up a sort of “table of

contents” for story structure. I would

change it drastically each quarter, but it’s generally built on the idea of

three-act structure, though I feel like the traditional second act is actually

three very distinct parts, the first two quarters each constituting their own section and the second half, creating

five acts, though not five acts in the Shakespearian format, where the true

complications arise in the second act (mine still pop up in the first).

Anyway, I began to use this in my own stories. My hope was to eventually perfect it as a

model which could be used on all of my projects, shaving off time and allowing

me to focus on the execution of details.

Painting a car instead of building it.

I even went so far as to assign page numbers to each stage of the

story. For example, from The Creeps:

Pages 51-59: First minor showdown with monster intertwined with supporting character’s arc

For the first time, the reader sees the monster and there is now certainty of what the Creeps face. In a monster story, this would kill the suspense – once you see the monster, it’s less scary. But this is a mystery, so we can now have fun depicting the monster while still eliciting the suspense of its motivations or origins.

The support character is involved in this event, and the encounter serves to highlight the moral need on the part of the Creeps to address whatever problem he or she may be facing.

Pages 51-59: First minor showdown with monster intertwined with supporting character’s arc

For the first time, the reader sees the monster and there is now certainty of what the Creeps face. In a monster story, this would kill the suspense – once you see the monster, it’s less scary. But this is a mystery, so we can now have fun depicting the monster while still eliciting the suspense of its motivations or origins.

The support character is involved in this event, and the encounter serves to highlight the moral need on the part of the Creeps to address whatever problem he or she may be facing.

The trouble with this is that it doesn’t work. In working out the outline I almost

immediately stray from the page numbers and end up omitting large sections, or

adding to them. It might work as a

starting point, but if the goal was to eliminate a step, then attempting to

composite a universal theory of narrative at the onset of every project means

that goal failed spectacularly.

But more than this:

In an effort to trim the narrative fat, I’m losing something. In a conversation I just had with Tony Cliff

(if you want to hear the part in which we talk about this, it starts around 1:12:50),

I found that one of the things that I was losing was tangential scenes. Fun bits, informative bits, sequences that do

nothing for narrative propulsion but which give warmth and color to a

tale. But that’s not the big thing.

I’m no longer thinking of scenes.

When I started making books, I would think about the time

period, the genre, and the location, and I would think about what scenes I

wanted in the book. I’d write them all

down on post-its and put them on a big posterboard and move them around and add

bits and pieces until there was a logical progression. A scene puzzle on a scene board. And that was it.

I don’t think I consider scenes anymore. At least, not at the forefront of crafting a

narrative.

And that’s lousy! I

like working towards fun, visual scenes. Without

them, this is a stiff, talking head medium.

And I think I’ve gotten so wrapped up in the mechanics of plot that I’ve

been neglecting that the narrative needs to work on a predominantly visual

level, and good scenes are visual scenes.

Locale and color direction and staging trump dialogue and emotion every

time. Not that they’re mutually

exclusive, but I’ve been so focused on the latter that I’m forced to consider

the former in the execution of the pages, making that part of the job a lot

more difficult (how do I make this info dump library scene visually compelling?). If I were going scene-first, they wouldn’t be

in a library. They’d be hanging on top

of a bookmobile on its way back from the VA hospital reading a heisted book that they've been expressly prohibited from checking out. Which of those two possibilities would you remember after you’d read it?

So the conclusion I’ve come to is this, though it will

likely change drastically as I attempt its implementation: Don’t write to

structure. At least, I shouldn’t, the way I have been.

Write to SCENES in your initial draft, THEN craft it to fit

the tight structure. There probably won’t

even be that much by way of changes, really, and it’ll keep those visually

iconographic moments key in your mind while you’re working.

Are there dangers here?

Absolutely. When something

artificially builds to what the creator intends to be a stay-with-you visual

scene, you can tell, and you can feel it (as Falynn Koch brought up in class years ago, the entirety of the library characters' storyline in Day After Tomorrow is clumsily intended to lead directly to the boat wolves scene). And working on hard genre stuff as I do

there’s always the temptation – a temptation to which I’ve succumbed in the

past – to knowingly or subconsciously borrow heavily from the visual

iconography of existing scenes from that genre.

There can be a way of doing that successfully (Gore Verbinski is an

example of a guy who explicitly borrows from visual genre conventions but does

so in a way that makes the work uniquely his own), but the balance between

originality and hearkening is one that has to be carefully struck. But I think the benefits outweigh the reservations; I’ll be giving the old scene board another go.

Tuesday, December 2, 2014

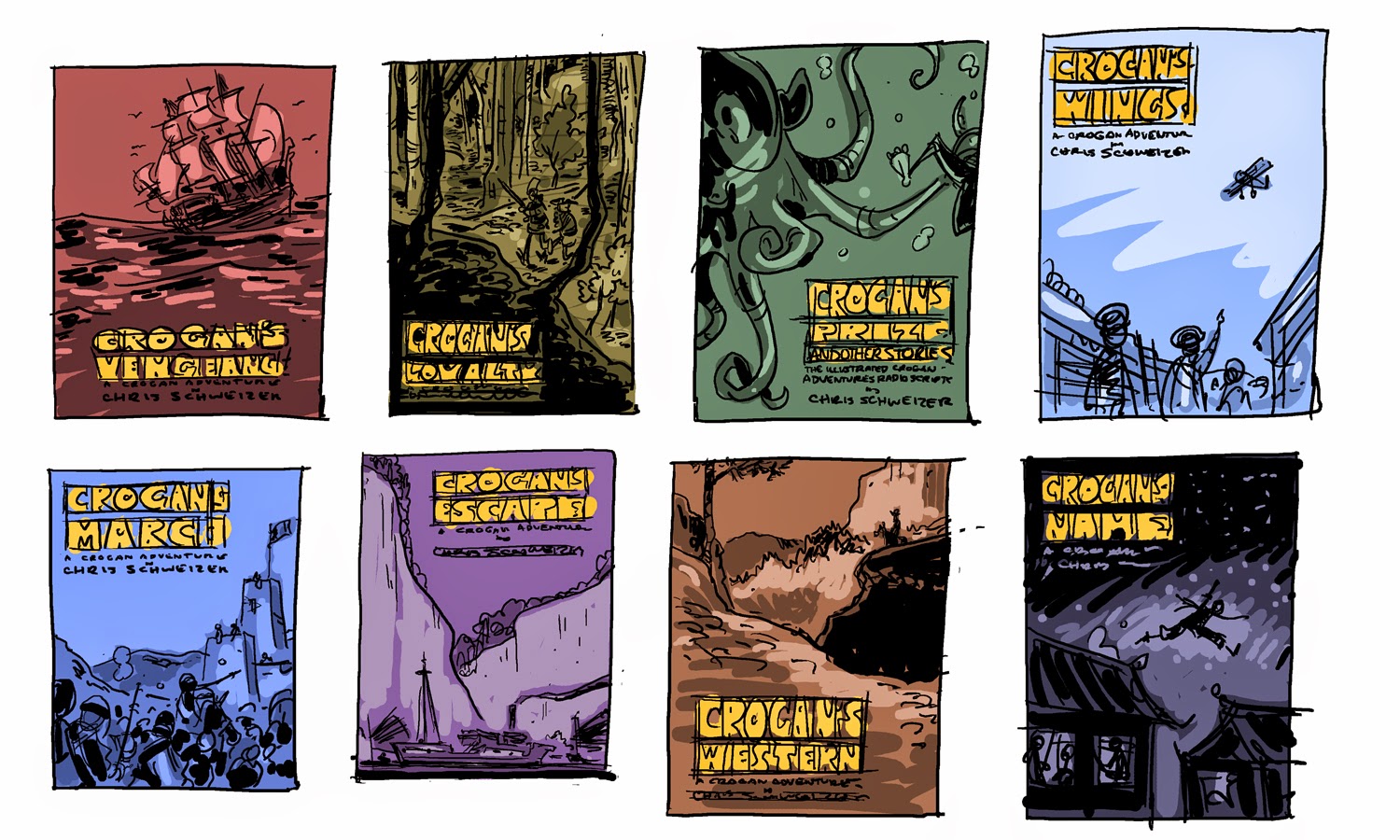

New Crogan Trade Dress

|

| Final cover for Volume 1 |

There have been a few reasons for this lack of updates. One is that I've been working on other projects. I have a middle reader horror series (The Creeps) coming out from Abrams Amulet in 2015 which I've been writing, drawing, and coloring with the intention of releasing two full-length books per year, and I've been doing animation design work for a couple of TV shows.

I have been working on Crogan stuff, too, but it's been under wraps. Though I've spoken about our intention to do so casually, we've never formerly announced that there will be color editions released of the existing Crogan Adventures books, and that's what's been taking most of my Crogan attention lately. Keeping it close to the vest until we've solicited the books was always an intention, and now that it's available for preorder I can come out and give the skinny.

I'll talk more at length about the decision to go to color on the existing books later this week. It was not made lightly.

Since the books are going to be different, we didn't want there to be any confusion on the part of readers when it came to what they were buying. So we decided to take the opportunity to make a new trade dress for the books. I'm working again with Keith Wood, who designed the original trade dress, and we decided to push the books in a more hand-done direction, eschewing type and logo for hand-lettering, as it better fits with the aesthetic of the pages themselves.

I went through a LOT of variations, trying to find one that would work. The original dress was inspired by the 1990s British Harper Collins trade paperback editions of George MacDonald Fraser's The Flashman Papers series, but I finally felt comfortable enough this go 'round in my own aesthetic that I didn't feel the need to play off of existing designs (though my current cover sensibility owes a great deal to principles that I've picked up by studying the work of my good friend Francesco Francavilla, whose masterful design skills and courage in the employment of loose hand has given me the approbation and confidence to tackle the use of text with a similar cavalarity).

I'd done mock-ups for covers of Crogan's Escape, which I had intended to serialize, and had enjoyed attempting to play with a limited palette. As I don't think i've posted these before, I'll post them now. They affected later decisions made.

I really liked the employment of the title anywhere, and considered trying to go this route with the new trade dress. Series consistency, though, would require a consistent color palette (at least by my reckon), and I didn't like that. Whatever colors are used on March would be a poor fit with Loyalty, and I expect that dissonance would only grow as new books came out.

But in the end, character wins out. After a lot of attempts, I finally hit what I thought might be a good foundation upon which to build the new trade dress:

My thought was that each book would consist of five colors: a consistent off-white, a consistent black, and a consistent tan that would be used on each cover. Then there would be a bold color for use in the title and to pull focus to the character depicted, and a background. The uniformity of the first three colors would tie the series together and a flexible template would help keep the designs tight.

You can see Francesco's influence here, in the inclusion of the publisher logo in the upper left corner. It's an old paperback standard that's started to come into vogue again (other folks besides Francesco, especially those with comic bends, make plenty of use of it, too), and I like it. When agreed to by the author I think it showcases an acknowledgment that publishing is just as much a commercial exercise as it is an artistic one. I think I've stated before that my definition of comics includes a clause stating that there is an intention of reproduction, and the publisher logo highlights this. Thematically, it ties in with my ideology, and I like the aesthetic a lot, too, especially if one is permitted to redraw the logo in one's own hand.

My editor didn't like the inclusion of the logo, and that's fair. They're the company putting out the book and me putting it on the cover is a little at odds with the creators-first reputation that they've worked to cultivate. Likewise, we had a lot of back-and-forth about whether to include a volume number. From a sales standpoint, it would probably help, encouraging retailers to keep the full range of books and prompting readers to fill in the gaps in their collection. But it might prevent a casual reader from picking up a volume that might interest him or her because it's not the first. As the books are written with the full intention of making each volume stand on its own, this is an important factor, and one which my editor championed. As of now, the prominent volume number has been removed, its only remnant a modest nod on the spine, for the ease of cataloguing ones' holdings (my hope is that I eventually make so many as to frazzle those with a collection as to their chronology). This, too, may end up getting the axe before press, but for now I think it a serviceable compromise between the two notions.

My editor (whom I keep mentioning without identifying, it's James Lucas Jones) approached a lot of retailers, sales reps, librarians, etc, to discuss what would be best for the books' reception: individual titles (Crogan's Vengeance, Crogan's March, etc) or a series title (The Crogan Adventures). The answer, across the board, was series title, with the individual titles being the names of each respective volume. Though this tightens the design a bit (I like the freedom of having to revisit the text each time) it is a charming notion, its only obstacle perhaps being that casual reader thing, and maybe award nods. But the latter is an ego concern that ought to be immediately dismissed. Another perk is that the series, called "The Crogan Adventures," might finally enter the lexicon of folks who like it; as it stands, folks call it anything from "The Crogan series" to "Crogan's Adventures" to "The Crogan Family Adventures," and any number of other variations. A fixed name might encourage uniformity, which might bolster easier recognition. This does, however, mean that my "(whoever) Crogan in" thing no longer works, which kind of bums me out. I liked that.

I went through a pass of Spines (included are the final cut):

The width of the spine (and estimated width on subsequent books) rendered pretty much all of these unusable, but the basis was there, notably in making the series name go from two lines to one.

Here's the first rough pass at the wraparound:

I used the roughs as the pencils for the solicitation cover:

And yesterday finished up the final cover and wraparound, still subject to editorial change and notes from Keith:

And I just realized that the West Indies thing on the front cover ought to be yellow-gold, not off-white. Oops! Time to edit and resubmit. Or maybe it's better off-white. Actually, it's kind of growing on me.

You may have noticed that the title of this particular installment is Catfoot's Vengeance rather than Crogan's Vengeance. The repeat of "Crogan" seemed a bit much, and I thought that completely departing from the original title might be better for series installments, but James (rightfully) was concerned that, was "Vengeance" not in the title, that readers might be confused and buy this thinking it a new book and not a reissue. I expect the third book will just be called "Loyalty," and I have no clue as to what the second one will be called. "March" always felt like a working title, and I'd like to come up with something a little more thematic, as it is, for better or worse, a more philosophical and meandering book than the others.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)